The Amarna Letters are a unique and invaluable collection of ancient diplomatic correspondence dating from around 1350 BCE, during the reigns of Egyptian Pharaohs Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten. These letters were discovered in 1887 in the ruins of Akhetaten—modern-day Amarna—the short-lived capital city founded by Akhenaten in Upper Egypt.

Origin and Discovery

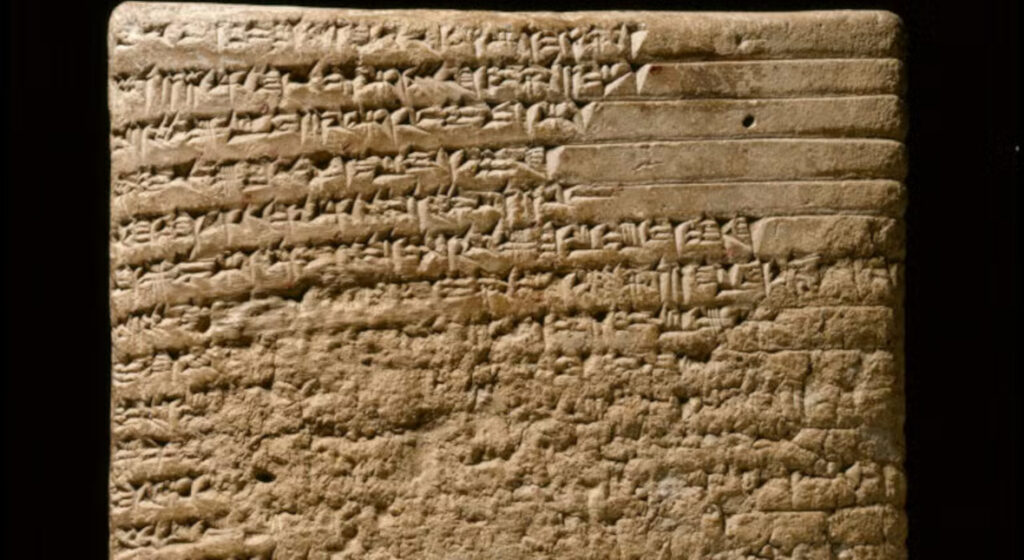

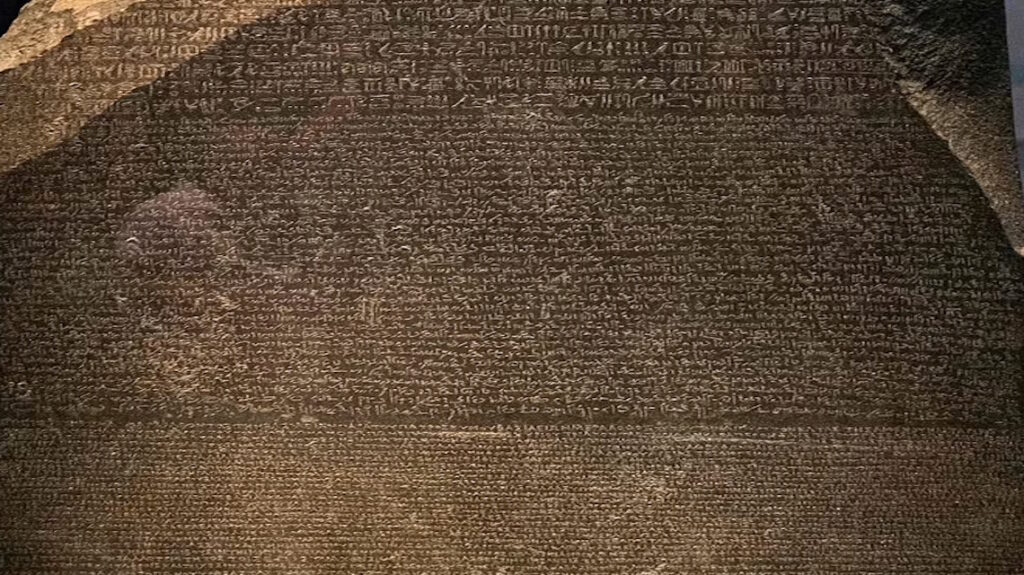

The letters are inscribed on small clay tablets using cuneiform script, the wedge-shaped writing system originally developed in Mesopotamia. Despite Egypt having its own writing system (hieroglyphs and hieratic script), Akkadian cuneiform was used because it was the established international language of diplomacy in the Late Bronze Age Near East.

The cache contains roughly 350 tablets, found in what archaeologists believe was the royal archive of the city, providing an unprecedented glimpse into international relations and diplomacy at a time when Egypt was one of the world’s superpowers.

Language and Script

The letters are written almost exclusively in Akkadian, the diplomatic lingua franca of the era, used by kingdoms stretching from Mesopotamia to the Levant and Egypt. This reflects the extensive cultural and political connections across the region, despite diverse local languages and scripts.

Some letters also include brief passages in local languages, such as Hurrian or Canaanite, but the primary diplomatic language was Akkadian.

Content and Correspondents

The Amarna Letters were primarily sent between:

-

The Egyptian Pharaoh’s court and

-

Foreign rulers, vassal kings, and city-state leaders

These correspondents came from regions including:

-

Canaan and Syria (modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and parts of Syria)

-

Babylonia and Assyria (Mesopotamia)

-

The Hittite Empire (Anatolia, modern-day Turkey)

-

Mitanni (a Hurrian kingdom in northern Syria)

-

Smaller city-states and polities throughout the Near East.

The letters cover a wide range of diplomatic topics, such as:

-

Requests for military aid or reinforcements against rival city-states or invading groups.

-

Negotiations over royal marriages, often arranged to secure alliances.

-

Exchange of gifts and tribute—a common practice to show respect and maintain good relations.

-

Complaints about political disputes, territorial conflicts, or disloyalty.

-

Reports on local conditions, threats, or rebellions.

The Amarna Letters are full of vivid personalities, political intrigue, and dramatic requests. Here are several interesting and memorable stories drawn from specific letters and their historical context:

Rib-Hadda of Byblos: The Desperate Vassal

Rib-Hadda, the king of Byblos (modern-day Lebanon), was one of the most prolific writers in the Amarna archive—he sent over 60 letters to the Pharaoh.

His Story:

-

Rib-Hadda’s letters are often desperate and emotional.

-

He constantly begs Egypt for military help, warning that his city is under siege by enemies and that rival kings are plotting against him.

-

He accuses other vassals of betraying Egypt and claims he has remained loyal even while starving.

-

At one point, he writes that he’s surviving on grass and that the Pharaoh’s inaction could lead to his death and the fall of Byblos.

Excerpt (paraphrased):

“I lie prostrate at your feet… Why do you not send archers to save your loyal servant? Shall I die while the Pharaoh delays?”

Outcome:

Despite his loyalty, Egypt never sent the support he begged for. Eventually, Rib-Hadda was dethroned, possibly killed, and replaced by a rival. His story is a tragic tale of abandoned loyalty and imperial overreach.

Royal Marriage Politics: Princesses and Power

One of the central themes in the Amarna Letters is the marriage diplomacy between great kings.

The Babylonian King’s Complaint:

Burna-Buriash II, King of Babylon, writes to Egypt complaining that he never received a proper dowry when his daughter married into the Egyptian royal family.

Excerpt (paraphrased):

“Why have you sent only two minas of gold? That is not fitting for a great king’s daughter. Do you think Babylon is poor?”

A One-Sided Policy:

Egypt refused to send Egyptian princesses abroad in marriage. Other kings constantly asked for Egyptian royal brides, but the Pharaohs would only accept foreign princesses and never gave their own in return—a powerful statement of Egypt’s superiority.

The Widow’s Plea to the Hittites: A Mystery Letter

After Akhenaten’s death, a mysterious letter was sent to Suppiluliuma I, King of the Hittites.

The Letter:

An unnamed Egyptian queen—likely Ankhesenamun, widow of Tutankhamun—wrote to Suppiluliuma, saying her husband had died and she had no heir. She shockingly asked him to send one of his sons to become Pharaoh.

Quote (translated):

“Never shall I take a servant of mine and make him my husband. I am afraid.”

The Fallout:

Suppiluliuma was suspicious but eventually sent his son Zannanza to Egypt. However, the prince never arrived—he was murdered en route. This likely ended the diplomatic relationship and may have triggered military conflict between Egypt and the Hittites.

This mysterious episode is one of the most dramatic and debated moments in Amarna-era history.

The Rise of the Habiru: Outsiders or Rebels?

Several letters refer to a threatening group known as the Habiru (or Apiru), who are attacking cities and causing instability in Canaan.

Who were the Habiru?

-

Possibly bands of displaced people, mercenaries, or rebels.

-

Some scholars have speculated they may be distantly related to the Hebrews of later biblical tradition, though this remains debated.

Letters from Canaanite rulers:

Kings like Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem write to Egypt saying that the Habiru are seizing territory, and if the Pharaoh doesn’t send help, Egypt will lose control over the region.

Excerpt (paraphrased):

“All the king’s lands are being taken by the Habiru. Will the Pharaoh sit idly while his cities fall?”

Golden Gifts and Royal Envy

Rulers loved Egyptian gold, and the Amarna Letters often sound like gift registries or complaint letters.

Mitanni’s Lavish Expectations:

Tushratta, king of Mitanni, complains that the gold statues sent from Egypt are not solid gold, as expected, but gold-plated wood.

Excerpt (translated):

“The statues you sent are not what you promised. Is this how you treat your ally?”

He even references past deals with Amenhotep III to pressure Akhenaten into sending more lavish gifts. The entire tone is one of keeping up appearances—and trying to outshine rival kings.