Discovered in 1908 near the small town of Willendorf in Austria, the Venus of Willendorf is one of the most famous and enigmatic artifacts of the Paleolithic era. Measuring just 11.1 centimeters (about 4.4 inches) in height, this limestone figurine is estimated to be around 25,000 to 30,000 years old, dating back to the Gravettian culture of the Upper Paleolithic period. Despite her diminutive size, she has had a massive impact on our understanding of prehistoric art and symbolism, challenging modern assumptions about early human culture, gender, fertility, and aesthetics.

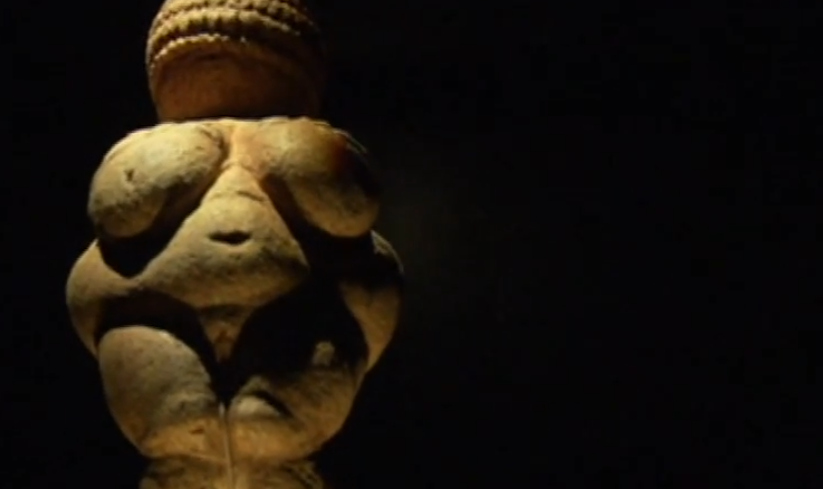

The Venus of Willendorf is part of a broader category known as “Venus figurines”, which have been found across Europe and parts of Eurasia. These small, carved figures typically depict female bodies with exaggerated sexual features—large breasts, wide hips, and prominent buttocks—often interpreted as symbols of fertility or abundance. However, each figurine is unique, and the Willendorf Venus stands out for the level of detail in its carving, the absence of facial features, and the distinctive coiled or braided hairstyle (or possibly a hat) that crowns her head.

Carved from oolitic limestone not native to the Willendorf area and tinted with red ochre, the Venus may have been transported over long distances, suggesting trade or movement among groups of early humans. The use of red ochre, a pigment associated with ritual and symbolism, supports the idea that the figurine was more than a mere toy or ornament. Scholars have debated her purpose for over a century: Was she a fertility idol, a goddess, a good-luck charm, or even an early form of self-representation?

One prevailing theory suggests that the exaggerated features of the Venus relate to fertility and reproduction, embodying a kind of prehistoric ideal of womanhood—well-nourished and able to bear children, essential qualities in an age where survival was uncertain. Some archaeologists argue that her lack of facial features and feet emphasizes universality, making her a symbolic figure rather than a portrait of an individual. Others propose that she may have been carved by women, even as a form of self-representation, since the view resembles what a woman might see looking down at her own body.

However, more recent scholarship has called for caution against overly simplistic or sexist interpretations. The label “Venus”—a reference to the Roman goddess of beauty—was imposed by 19th- and early 20th-century male archaeologists and reflects modern biases about beauty, gender, and sexuality. Critics argue that calling her a “Venus” imposes a Eurocentric and patriarchal framework on a figure created by a society whose values may have been vastly different. Instead, they urge interpretations that consider context, function, and social meaning, without projecting modern assumptions onto the past.

The figurine’s mysterious nature is part of what makes her so compelling. She offers a rare glimpse into the symbolic life of early Homo sapiens, long before the advent of written language or organized civilization. The fact that such a small and delicate object has survived for over 25,000 years is a testament to both its craftsmanship and its potential significance to the people who made and carried it. Whether she was worn, worshipped, or simply cherished, the Venus of Willendorf invites us to imagine a world very different from our own—yet fundamentally human in its search for meaning.

Today, the Venus of Willendorf is housed in the Natural History Museum in Vienna, where she remains a centerpiece of prehistoric art.