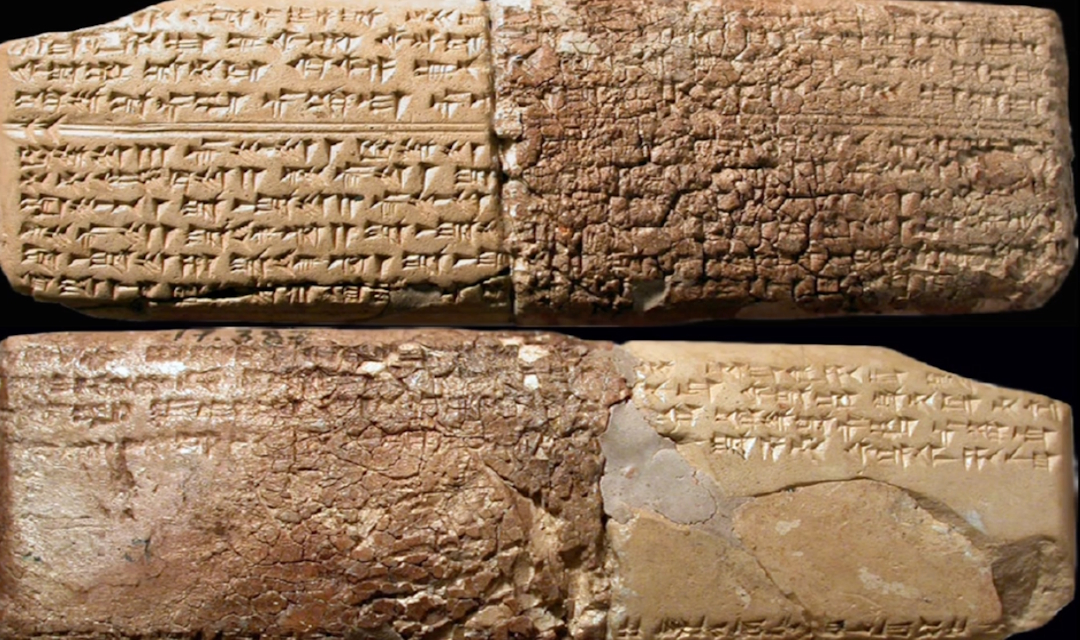

The Hurrian Hymns represent one of humanity’s most astonishing intellectual achievements: the moment when sound itself was translated into symbols. Discovered in the ancient port city of Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra, Syria), these clay tablets date to around 1400 BCE, during the Late Bronze Age—a period of intense cultural exchange across the eastern Mediterranean. At a time when writing was still rare and laborious, someone believed music was important enough to be preserved permanently in clay.

Music Written into Stone and Clay

The hymns are written in cuneiform, a wedge-shaped script pressed into soft clay using a reed stylus. Unlike alphabetic writing, cuneiform allowed information to be encoded spatially and numerically, making it surprisingly well-suited for early musical notation. The tablets include song lyrics alongside technical musical instructions, making them the earliest surviving documents in which language and music coexist as a single written system.

Among the fragments, Hurrian Hymn No. 6 is nearly complete. This alone is extraordinary—most ancient music survives only as theoretical commentary or scattered references. Here, however, we have something approaching a score, albeit one that requires interpretation.

The hymn is dedicated to Nikkal, a goddess associated with orchards, fertility, and divine order. In agrarian societies, fertility was not symbolic—it was survival. Music, therefore, functioned as a technology of ritual, believed to influence divine forces through sound.

A Multilingual Musical System

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Hurrian Hymns is their linguistic layering. The lyrics are written in Hurrian, a language isolate unrelated to Semitic or Indo-European tongues. The musical instructions, however, use Akkadian technical terms, the scholarly and diplomatic language of the time.

This reveals something remarkable: music theory had already become international. Just as modern musicians use Italian terms like allegro or forte, Bronze Age musicians relied on Akkadian terminology to communicate musical structure. This suggests the existence of a shared theoretical framework, transmitted across cultures long before modern science formalized acoustics.

How the Hurrians Actually Wrote Music

The Hurrian Hymns, inscribed on clay tablets in the ancient city of Ugarit around 1400 BCE, represent the oldest known written music in human history. Unlike modern notation systems that fix precise pitch and rhythm, the Hurrian notation is far more relational. It does not tell performers exactly which note to play at what moment, nor does it specify tempo or rhythm. Instead, it encodes the relationships between notes, intervals, and strings on the lyre.

What the tablets specify:

-

Intervals between strings, telling the performer how the notes relate to each other rather than their absolute frequencies.

-

Tuning sequences for the lyre, so that the instrument could be set up in a consistent framework for performance.

-

The names of the strings, allowing musicians to follow the melody methodically.

-

The order of performance—essentially a guide to the melodic contour, ensuring the hymn could be reproduced accurately from one performer to the next.

What the tablets do not specify:

-

Exact pitch height: there is no instruction like “play C here” or “play E there.” The precise frequency was left to the performer’s ear.

-

Tempo: the speed of performance is left entirely up to the musician, probably guided by ritual, tradition, or intuition.

-

Explicit rhythm: the timing of notes, accents, and pauses is not documented, highlighting a profound difference in how music was conceptualized in oral cultures.

This absence is not a limitation, but a window into an ancient understanding of music. The Hurrians prioritized relationships and harmonic structure over absolute precision, reflecting a practical approach: record what is hard to remember, and leave the rest to human memory and embodied performance.

The Physics Behind Hurrian Music

At the heart of the Hurrian system lies acoustics—the physical laws governing sound—even though these were never formalized mathematically at the time.

When a string vibrates:

-

Pitch is determined by its frequency, which is how fast it vibrates.

-

Frequency depends on three main factors: the string’s length, its tension, and its mass.

-

Halving the length of a string doubles the frequency, producing an octave, one of the most fundamental intervals in all of music.

-

Simple ratios such as 2:1 (octave), 3:2 (perfect fifth), and 4:3 (perfect fourth) produce consonant intervals that are naturally pleasing to the human ear.

These relationships are not cultural inventions or arbitrary preferences; they are direct consequences of physics. In fact, the Hurrian tuning system aligns closely with what modern music theory calls the diatonic framework, suggesting that these ancient musicians had already discovered the same harmonic principles that later Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras would attempt to formalize.

The Hurrians achieved this understanding through careful experimentation and attentive listening, not through abstract speculation. They tuned, plucked, adjusted, and documented what worked, producing a system that was both practical and harmonically coherent. The clay tablets capture this empirical knowledge, bridging the gap between practical musicianship and early theoretical insight.

Why Rhythm Was Left Unwritten: A Neuroscience Perspective

One of the most intriguing features of the Hurrian Hymns is the absence of written rhythm, a choice that can be illuminated through modern neuroscience and cognitive science.

Human brains are naturally adept at remembering rhythm:

-

Rhythm activates the motor cortex, linking musical timing to movement, gesture, and even breathing patterns.

-

It is deeply ingrained in the body through repetition and ritual, enabling precise reproduction without external cues.

-

In oral cultures, rhythm is often embodied knowledge, passed from performer to performer through experience rather than inscription.

Writing down rhythm may have seemed redundant—or even counterproductive. By contrast, pitch relationships are far more abstract and difficult to retain accurately, making them ideal candidates for documentation. The Hurrians intuitively understood the division of labor between memory and notation: record what is fragile and easily forgotten, leave the rest to human skill and embodied knowledge.

This approach reflects a broader principle in ancient oral cultures: music was as much a social and physical practice as it was an intellectual one. Performers internalized rhythm through training, ritual, and repetition, while notation served as a scaffold for harmonic structure and melodic continuity.

Instruments as Acoustic Technology

The hymns reference a lyre, an instrument central to Mesopotamian music. Lyres were not primitive objects; they were carefully engineered acoustic devices. The wooden soundbox amplified vibrations, while gut strings allowed precise tuning. Some lyres were inlaid with precious metals, indicating their sacred status.

From a scientific perspective, the lyre functioned as a resonance system, converting mechanical energy into sustained sound waves. Ancient musicians learned how different materials, string thicknesses, and tensions affected tone—knowledge accumulated through generations of trial and error.

Reconstructing an Ancient Soundscape

Because the notation is indirect, modern reconstructions of the Hurrian Hymns vary. Some interpretations produce slow, meditative melodies; others sound unexpectedly lively. This uncertainty highlights a profound truth: music exists between mathematics and emotion. The tablets give us structure, but interpretation gives them life.

Yet scholars overwhelmingly agree on one point: this is written music, not poetic metaphor or theoretical abstraction. It represents the earliest known attempt to externalize musical knowledge, freeing it from individual memory and allowing it to persist across centuries.

Other Early Musical Evidence (Not Fully Written Music)

1. Mesopotamian Music Theory Tablets (c. 1800–1500 BCE)

Older Babylonian tablets describe:

-

String tunings

-

Musical intervals

-

Scale systems

However, these tablets explain music rather than record a specific song.

2. Ancient Greek Musical Notation (c. 500–200 BCE)

The Greeks developed a clearer notation system using letters. The most famous example is:

-

The Seikilos Epitaph (c. 100 BCE–100 CE)

This is the oldest complete written melody from antiquity that we can perform with relative confidence.

Hurrian Hymn No. 6: A Note-by-Note Journey Through Ancient Sound

The Hurrian Hymn No. 6, discovered on a clay tablet in Ugarit around 1400 BCE, is the oldest surviving example of written music in the world. Its notation differs radically from modern musical systems: it does not fix exact pitches, nor does it specify tempo or rhythm. Instead, it records intervals, string tunings, and relative note sequences, reflecting how ancient musicians thought about sound—through relationships, resonance, and ritual function.

Here, we explore a reconstructed version of the hymn, analyzing each phrase as degrees within a heptatonic scale. Modern note names like “C” or “D” are not used; instead, we focus on intervallic motion and the emotional, cognitive, and acoustic effects of each step.

1. The Tuning Framework (Before the First Note)

The first step in understanding the hymn is to reconstruct its tuning. Scholar Anne Draffkorn Kilmer proposed that the lyre was tuned according to a seven-note scale, inspired by Babylonian interval theory. This heptatonic framework forms the basis for all subsequent melodic movement:

Scale degrees: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Even though we do not know the starting pitch, the emotional and cognitive power of the hymn comes from how the notes move relative to each other, not the absolute sound.

Scientific insight:

-

The intervals are based on consonant frequency ratios (like 2:1 for octaves, 3:2 for fifths, 4:3 for fourths), meaning the music resonates naturally with the human auditory system.

-

The Hurrians discovered these relationships empirically, creating music that is harmonically pleasing without formal theory.

2. Opening Phrase — Establishing the Sonic Center

Notes: 5 → 4 → 3

What’s happening:

The hymn opens with a descending motion, which immediately grounds the listener. Descending intervals are typical in ritual music because they signal stability, gravity, and sacred space.

Acoustic effect:

-

Descending sequences reduce neural tension, creating a sense of calm and attentiveness.

-

This mirrors natural vocal patterns of invocation and prayer, which tend to descend to draw attention inward.

Neuroscience note:

-

Descending motion engages prediction networks in the brain, signaling safety and expectation fulfillment.

-

The listener intuitively feels that the space is solemn and sacred.

3. Second Phrase — Gentle Expansion

Notes: 3 → 4 → 5

What’s happening:

This phrase mirrors the opening descent but ascends instead, creating symmetry and a sense of “breathing outward.” It balances the melodic flow while reinforcing the tonal center.

Cognitive insight:

-

Symmetry in intervals helps anchor memory, which is crucial in oral traditions.

-

Palindromic interval patterns, like this one, appear in early ritual music across cultures, suggesting an intuitive understanding of musical structure.

Musical function:

-

This phrase acts as a bridge between grounding and ascent, ensuring the hymn feels coherent without requiring explicit rhythmic notation.

4. Third Phrase — The First Emotional Lift

Notes: 5 → 6 → 7

What’s happening:

The melody climbs higher than before, reaching the first peak. This ascent signals petition, praise, or invocation—likely directed toward the goddess Nikkal.

Emotional effect:

-

Rising intervals increase arousal and attention.

-

The brain perceives upward motion as intentional emphasis, marking this as a moment of spiritual importance.

Scientific observation:

-

Ascending melodic motion activates reward-related neural pathways, creating a subtle sense of anticipation and engagement.

5. Cadential Drop — Controlled Resolution

Notes: 7 → 5

Why this matters:

-

Instead of returning fully to the tonic (degree 1), the melody drops by a third, creating suspended reverence.

-

This technique prevents finality, keeping the musical ritual open-ended.

Acoustic insight:

-

Dropping a third instead of an octave allows string resonance to decay naturally, producing a gentle, continuous soundscape.

-

It demonstrates sophisticated compositional thinking: even without explicit theory, the Hurrians manipulated tension and release intentionally.

6. Middle Section — Repetition with Variation

Notes: 5 → 4 → 3 → 4 → 5

What’s happening:

-

Repetition anchors memory, while variation keeps the listener engaged.

-

Oral cultures rely on this balance to ensure music is both memorable and dynamic.

Cognitive science:

-

The brain prefers predictable patterns to track the melody.

-

Slight variations maintain interest and enhance memorability through pattern recognition.

Cultural insight:

-

Repetition with variation is a hallmark of ritual chants, allowing performers to internalize complex melodies without written rhythm.

7. Climactic Phrase — Highest Emotional Point

Notes: 5 → 6 → 7 → 6

Why this is crucial:

-

The melody peaks and immediately descends, creating an emotional arc akin to a call-and-response with the divine.

-

This rise-and-fall mirrors human emotional response in ritual, conveying petition, attention, and acknowledgment.

Neuroscience insight:

-

Ascending peaks activate arousal networks, while descending motion signals resolution and satisfaction, producing a complete emotional cycle in the listener.

8. Final Phrase — Grounding and Closure

Notes: 5 → 4 → 3

What’s happening:

-

Returns to the opening descent, creating a circular form that implies continuity rather than a final ending.

-

This non-teleological approach reflects ritual repetition: the hymn is meant to loop, not conclude, symbolizing eternal devotion.

Acoustic and cognitive insight:

-

The return to familiar intervals reinforces memory and provides a sense of completion without the need for closure.

-

Listeners experience ritual reinforcement, deepening engagement and spiritual resonance.

Structural Summary (Modern Interpretation)

| Section | Function | Interval Behavior | Emotional/Cognitive Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opening | Establish sacred space | Descending | Grounded, solemn, neural calm |

| Early phrases | Stabilization | Symmetry | Predictable yet engaging |

| Middle | Invocation | Ascending | Attention, petition, arousal |

| Climax | Divine contact | Peak + fall | Emotional apex, acknowledged invocation |

| Ending | Ritual closure | Descending | Circular form, memory reinforcement |

Hurrian Hymn No. 6 Note-by-Note Comparison of Two Reconstructions

Reconstruction A — Anne Draffkorn Kilmer (1970s)

-

Assumes a diatonic, heptatonic scale

-

Interprets the tablet as melodic notation

-

Produces a stepwise, chant-like melody

-

Most often performed and recorded

Reconstruction B — Marcelle Duchesne-Guillemin / Richard Dumbrill

-

Treats the tablet as a harmonic / tuning instruction

-

Emphasizes string transitions, not melody

-

Produces a more static, drone-centered sound

-

Closer to ritual soundscape than “song”

Think of this as:

-

A = melody-first

-

B = tuning-first

Shared Starting Assumptions (Important)

Both reconstructions agree on:

-

A lyre with named strings

-

Interval relationships derived from Babylonian theory

-

A descending–ascending ritual structure

-

Repetition and symmetry

The disagreement is how the instructions are meant to be performed.

Phrase-by-Phrase, Note-by-Note Comparison

Opening Phrase

| Function | Kilmer (A) | Dumbrill (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Notes | 5 → 4 → 3 | 5 → 5 → 4 |

| Motion | Clear descent | Partial sustain then descent |

| Effect | Solemn invocation | Drone-anchored gravity |

Interpretation difference

-

A hears intentional melodic descent

-

B hears a ritual anchoring note before movement

Cognitive effect:

-

A feels narrative

-

B feels spatial and meditative

Phrase 2 — Stabilization

| Function | Kilmer (A) | Dumbrill (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Notes | 3 → 4 → 5 | 4 → 5 → 5 |

| Motion | Symmetrical rise | Minimal movement |

| Effect | Balance, memorability | Sonic grounding |

Key disagreement

Is symmetry melodic intent (A) or tuning confirmation (B)?

Phrase 3 — First Lift

| Function | Kilmer (A) | Dumbrill (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Notes | 5 → 6 → 7 | 5 → 6 → 6 |

| Motion | Full ascent | Ascent with restraint |

| Effect | Emotional rise | Controlled tension |

Music theory note:

-

A allows a leading-tone effect

-

B avoids it, consistent with non-teleological ritual music

Cadential Drop

| Function | Kilmer (A) | Dumbrill (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Notes | 7 → 5 | 6 → 5 |

| Interval | Larger drop | Smaller, safer drop |

| Effect | Expressive release | Ritual continuity |

Here is a major philosophical split:

-

A treats climax as expressive

-

B avoids emotional “resolution” entirely

Middle Repetitive Section

| Function | Kilmer (A) | Dumbrill (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern | 5 → 4 → 3 → 4 → 5 | 5 → 4 → 5 → 4 |

| Structure | Arch-shaped melody | Oscillating tones |

| Effect | Memory + variation | Hypnotic repetition |

Neuroscience insight:

-

A activates prediction + surprise

-

B induces trance-like entrainment

Climactic Phrase

| Function | Kilmer (A) | Dumbrill (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Notes | 5 → 6 → 7 → 6 | 5 → 6 → 5 |

| Peak | Clear highest pitch | No true peak |

| Effect | Prayer answered | Prayer sustained |

This is the most debated moment.

-

If the hymn climaxes, Kilmer is right

-

If it circles, Dumbrill is right

Final Phrase

| Function | Kilmer (A) | Dumbrill (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Notes | 5 → 4 → 3 | 5 → 4 → 4 |

| Ending | Return and closure | Non-ending |

| Meaning | Completion | Continuation |

Structural Comparison

| Feature | Kilmer (A) | Dumbrill (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Melody | Clear | Minimal |

| Emotion | Expressive arc | Ritual stasis |

| Rhythm | Implied chant | Free / drone |

| Goal | Performable song | Sacred sound field |

| Modern feel | Familiar | Alien |

Which Is More “Correct”?

Scientifically honest answer:

Both are defensible.

-

The tablets do encode intervals

-

They do reference string order

-

They do not say how fast or expressively to play

So the real question is cultural:

If Hurrian music was:

-

Narrative & devotional → Kilmer fits

-

Ritual & cosmological → Dumbrill fits

Many scholars now suspect the truth lies between:

The Hurrian Hymns stand as a profound reminder that more than three thousand years ago, music was already being treated as a discipline worthy of preservation, study, and reverence. Long before concert halls or recordings, ancient musicians were laying the foundations of musical notation, ensuring that their sacred sounds could echo far beyond their own time.