Long before electronic computers, logic circuits, or software languages, one of the earliest steps toward programmable machines unfolded quietly in the workshops of early nineteenth-century France. Joseph Marie Jacquard, a humble weaver from Lyon, created a loom capable of automatically producing intricate textile patterns. What set Jacquard’s loom apart was not merely its mechanical brilliance, but its conceptual revolution: the separation of instructions from the machine itself. The idea that a machine could follow instructions encoded externally would later form the foundation of computing.

Before Jacquard, weaving complex fabrics required highly skilled artisans. In particular, a “drawboy” manually lifted warp threads according to memorized or written patterns. The loom itself had no flexibility; any change in pattern required retraining, reconfiguration, or human improvisation. Legend has it that some drawboys, bored by repetitive work, would intentionally mis-lift threads to create subtle pranks in the fabric—little jokes that only their fellow weavers could spot. Jacquard’s loom, by contrast, made such tricks impossible.

Jacquard’s solution was elegantly simple: punched cards. Each card represented one row of the textile pattern. Holes dictated which warp threads to lift, while solid sections kept the thread down. When fed sequentially into the loom, the cards directed the machine to reproduce complex patterns automatically. Early on, some weavers joked that the loom was “possessed,” because it could continue weaving perfectly even if the operator stepped out for a coffee. One particularly imaginative weaver reportedly claimed that Jacquard must have trained a tiny invisible army of monkeys to control the loom.

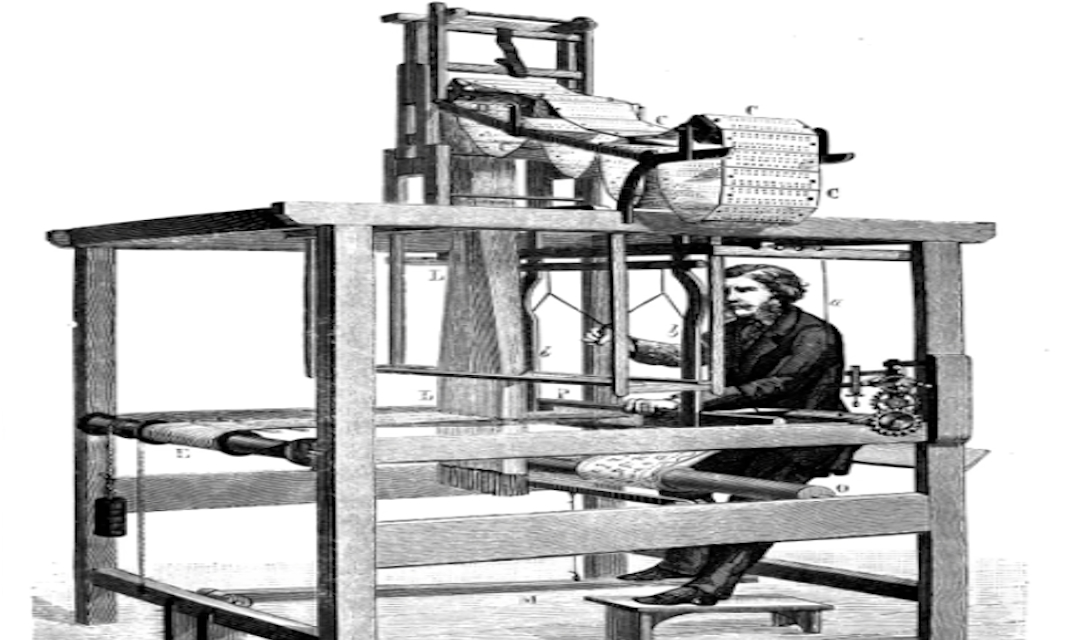

Mechanically, the loom was a marvel of clever design. Each warp thread passed through a hook connected to a heddle. A stack of punched cards passed over a row of needles; if a needle fell into a hole, the corresponding hook rose, lifting the thread. If the card was solid, the hook remained stationary. A shuttle passed the weft thread through, forming the completed row of the pattern. Row by row, the loom “read” the instructions, reproducing intricate designs automatically. Watching the mechanism in motion was hypnotic—some visitors remarked that it looked like “a perfectly choreographed dance of tiny metal fingers, each following a hidden conductor who preferred silk to music.”

The loom’s binary logic—lift or not lift, hole or no hole—foreshadowed modern digital computing. Each hook faced a simple yes/no decision, creating a mechanical form of conditional execution. Its modular and reusable design meant patterns could be stored, copied, or rearranged, giving a single loom virtually infinite flexibility. A humorous anecdote tells of an apprentice who fed the machine a random pile of punched cards as a joke. The result was an abstract pattern that resembled a squirrel holding a teapot, delighting some observers and confusing the others.

Jacquard’s invention provoked intense resistance. Skilled weavers feared the machine would render them obsolete. In Lyon, angry mobs smashed looms and chased Jacquard from his workshop. Some weavers, attempting to sabotage the loom, reportedly hid coins or sausages inside the shuttle mechanism. The loom, oblivious to human mischief, carried on weaving flawlessly. Witnesses joked that the loom had “better discipline than any apprentice” in the city.

These episodes mark one of the first recorded instances of technological anxiety, a human fear of being replaced by machines—a theme that echoes through the Industrial Revolution and even today with AI and robotics.

Despite this resistance, Jacquard’s ingenuity caught the attention of Napoleon Bonaparte. During a demonstration, Napoleon leaned so closely to inspect the mechanism that Jacquard’s assistant whispered to keep back—rumor has it the remark made the emperor chuckle. Napoleon recognized the loom’s broader significance, granting Jacquard a pension and royalties for each loom produced. This official endorsement helped spread the invention across Europe.

Jacquard’s work was also a quiet triumph of humility. He was not an abstract theorist but a practical problem solver, concerned primarily with reliability and efficiency. Yet his loom inspired far-reaching intellectual developments. Charles Babbage, decades later, drew directly from Jacquard’s concept of punched cards controlling a machine to design his Analytical Engine. Babbage famously remarked that his machine could “weave algebra just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.”

Ada Lovelace extended Babbage’s insight further. She realized that a machine could manipulate any symbolic content, not just numbers. Lovelace humorously imagined a future where machines could compose music, write poetry, or even create abstract visual art—though, she noted, they would likely never complain or ask for coffee breaks. In her vision, Jacquard’s abstraction had evolved into a universal language of computation.

The loom persisted in industrial use well into the twentieth century. Early data-processing machines, including Herman Hollerith’s census tabulators, borrowed Jacquard’s punched-card principle. Even today, digital artists and programmers use algorithms that trace conceptually back to the same logic: external instructions guiding precise operations. Some modern museum visitors, seeing the Jacquard loom in motion, joke that it was “the first office worker who never called in sick, never complained, and occasionally produced accidental abstract art.”

Jacquard’s loom also influenced design humor. Some factory supervisors created intentionally absurd “practice cards” to see what patterns the loom would weave, resulting in bizarre textile motifs reminiscent of surrealist art centuries before its time. A card sequence depicting an upside-down rooster once caused a visiting noblewoman to burst out laughing, exclaiming that the fabric looked like it had “a mind of its own.”

Even within Jacquard’s workshop, stories abound of the loom seemingly “outsmarting” its operators. One assistant reportedly tried to teach the machine to produce two different patterns simultaneously by stacking cards haphazardly. The loom ignored the experiment, producing a chaotic but strangely appealing pattern instead. Workers joked that the loom had “taste and discipline” far beyond the humans around it.

Joseph Marie Jacquard did not set out to invent computing. He sought efficiency, consistency, and beauty in cloth. Yet in doing so, he gave humanity something far greater: the first machine that obeyed abstract logic encoded outside itself.