When we hear the word blockchain, images of futuristic digital finance, cryptographic puzzles, and decentralized networks spring to mind. But at its heart, blockchain is simply a tool for recording and securing information in a way that ensures trust, permanence, and transparency. That same problem—how to record data so that it remains reliable across time and space—confronted humanity thousands of years ago in Mesopotamia. There, in the fertile valleys between the Tigris and Euphrates, the world’s first urban societies pioneered a system of clay tablets that in many ways prefigured the logic of blockchain.

The Birth of Writing as a Ledger

The earliest forms of writing, developed around 3300 BCE in Uruk, were not poetry or epics but lists: grain tallies, livestock counts, and receipts for trade. These early cuneiform marks were less about storytelling than accountability. Like blockchain’s first application in Bitcoin, writing began as a ledger—a record of exchanges that had to be reliable. Just as Satoshi Nakamoto envisioned blockchain as a solution to the “double-spending problem,” Mesopotamian scribes invented cuneiform to solve the problem of memory and trust in a growing economy.

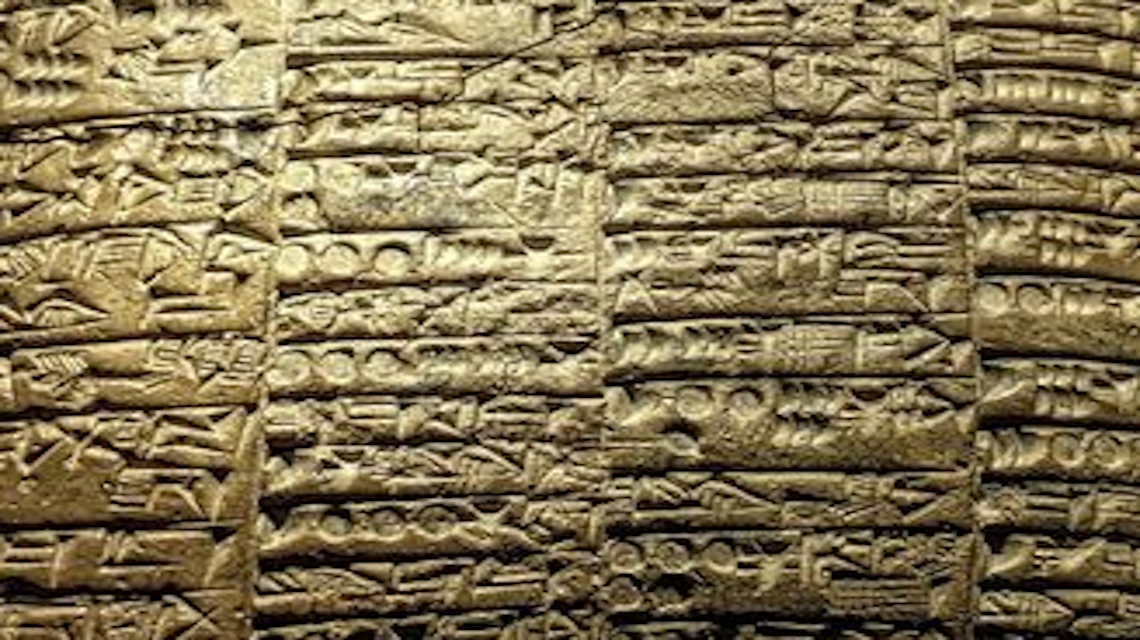

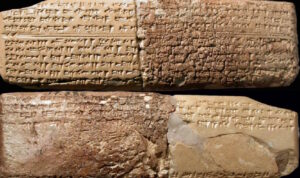

Clay as the First Immutable Medium

Why clay? Because it was cheap, abundant, and, most importantly, durable. Wet clay could be shaped into tablets, inscribed with a stylus, and then dried or fired. Once hardened, the text became permanent. To alter it meant destroying the object itself. In a sense, every clay tablet was an uneditable block of information. Just as altering a blockchain record requires rewriting the entire chain across countless computers, altering a clay tablet required visible, physical tampering that left unmistakable traces. This permanence gave tablets legal authority and made them the backbone of Mesopotamian administration.

The Temple as a Node in the Network

Blockchain relies on decentralized nodes—computers that collectively maintain and verify the ledger. In ancient Mesopotamia, temples played a similar role. They were not only religious centers but also economic and administrative hubs, storing vast archives of tablets. A temple might keep multiple copies of contracts, while other institutions or households held duplicates. This created redundancy, much like blockchain’s distributed ledger. Even if one archive burned or was looted, copies elsewhere preserved the record.

Authentication Through Seals and Witnesses

Where blockchain uses cryptographic hashing and digital signatures, Mesopotamians used cylinder seals and witnesses. Each seal was carved with intricate, unique designs and rolled across wet clay, leaving an unmistakable impression. Seals authenticated documents much like cryptographic keys do today. Additionally, contracts often listed multiple witnesses who could verify the agreement. Together, seals and witnesses functioned as layers of analog encryption and consensus mechanisms, ensuring that no single party could forge or alter a record without detection.

The Social Problem of Trust

At its core, blockchain exists because strangers cannot always trust one another. Similarly, Mesopotamian trade networks stretched across cities and regions, linking people who had no personal bond. How could a merchant in Uruk trust a supplier from Mari? How could a farmer prove repayment of a loan years after the agreement? The answer lay in clay tablets. By externalizing trust into a medium that all could verify, Mesopotamian society created a foundation for commerce, law, and governance. Blockchain does the same today: it replaces personal trust with systemic trust.

Transparency and Public Access

Clay tablets were often meant to be public. Legal decrees and contracts could be read aloud in markets or displayed in public places. In court disputes, scribes could bring forth tablets from archives as evidence. Some records—like Hammurabi’s famous Code—were deliberately placed in plazas so that no citizen could claim ignorance. This open accessibility is strikingly similar to blockchain’s principle of transparency, where ledgers are available for anyone to inspect. Both systems create security not by hiding information but by making it universally verifiable.

Smart Contracts, Ancient Style

Today, blockchain enthusiasts celebrate “smart contracts”—digital agreements that execute automatically when conditions are met. Remarkably, Mesopotamian tablets contained similar logic. A debt tablet might specify: “If repayment is not made by the harvest, collateral shall pass to the creditor.” These clauses encoded conditional outcomes into the contract itself. Once written, they became binding and enforceable, much like smart contracts running on Ethereum today. Though the medium was clay, not code, the principle of embedding obligations directly into the record was the same.

The Chain of Custody: Clay Envelopes

Another fascinating innovation was the use of clay envelopes. Important contracts were often enclosed within a clay casing, which bore duplicate inscriptions and seal impressions. If tampering occurred, the broken envelope exposed the original tablet inside. This was a physical precursor to blockchain’s chain of custody: tampering broke the link. Just as altering a blockchain transaction breaks the hash chain, altering a tablet destroyed the protective casing, making fraud obvious to all.

Hammurabi’s Code as a Public Blockchain

Around 1750 BCE, King Hammurabi of Babylon inscribed his laws on large stone stelae and distributed them throughout his empire. These laws were also copied onto clay tablets and stored in archives. Hammurabi’s Code functioned like a public blockchain: immutable, decentralized across multiple locations, and transparent to the people. Even rulers were bound by it, since the record could not be secretly altered. This made law not a matter of memory or decree but a fixed, verifiable ledger.

Endurance Across Millennia

Perhaps the strongest argument for clay tablets as proto-blockchain lies in their survival. Blockchain promises permanence, but Mesopotamian tablets have already proven it. Archaeologists have unearthed tablets that still clearly display contracts, inventories, and tax accounts written more than 4,000 years ago. These ancient ledgers remain readable even after millennia of burial. Few modern storage systems can boast such resilience. In effect, clay tablets achieved the ultimate test of immutability: survival through time.

The Evolution of Record-Keeping

From clay tablets, humanity moved to papyrus, parchment, and paper. Each new medium offered greater efficiency but less permanence. Archives burned, documents decayed, and histories were lost. Blockchain represents a return to the original Mesopotamian ideal: information that cannot be erased, manipulated, or forgotten. Where Mesopotamians used fire-hardened clay, we now use cryptographic mathematics. The medium differs, but the goal is identical: to write truth into a permanent, tamper-proof form.

Conclusion: A Timeless Human Problem

Both Mesopotamian clay tablets and blockchain address the same human need: how to record, secure, and trust information in a complex society. While one uses clay and seals and the other employs cryptography and algorithms, the underlying principle is strikingly similar. The story of blockchain, then, is not just a tale of digital revolution—it is also a continuation of a 5,000-year-old tradition begun in the fertile valleys between the Tigris and Euphrates.