For over a thousand years, Egyptian hieroglyphs were a silent code. Birds, snakes, twisted lines, and abstract symbols adorned tombs, temples, and obelisks along the Nile, yet their meaning was lost to the ages. To generations of travelers, adventurers, and scholars, hieroglyphs appeared magical—enigmatic decorations that hinted at the grandeur of a civilization but conveyed nothing intelligible. Some believed the writing was purely symbolic, intended only for the gods, while others speculated that the symbols contained hidden knowledge or mystical formulas. Despite centuries of speculation, Egypt’s language lay dormant, locked behind the visual complexity of its writing system.

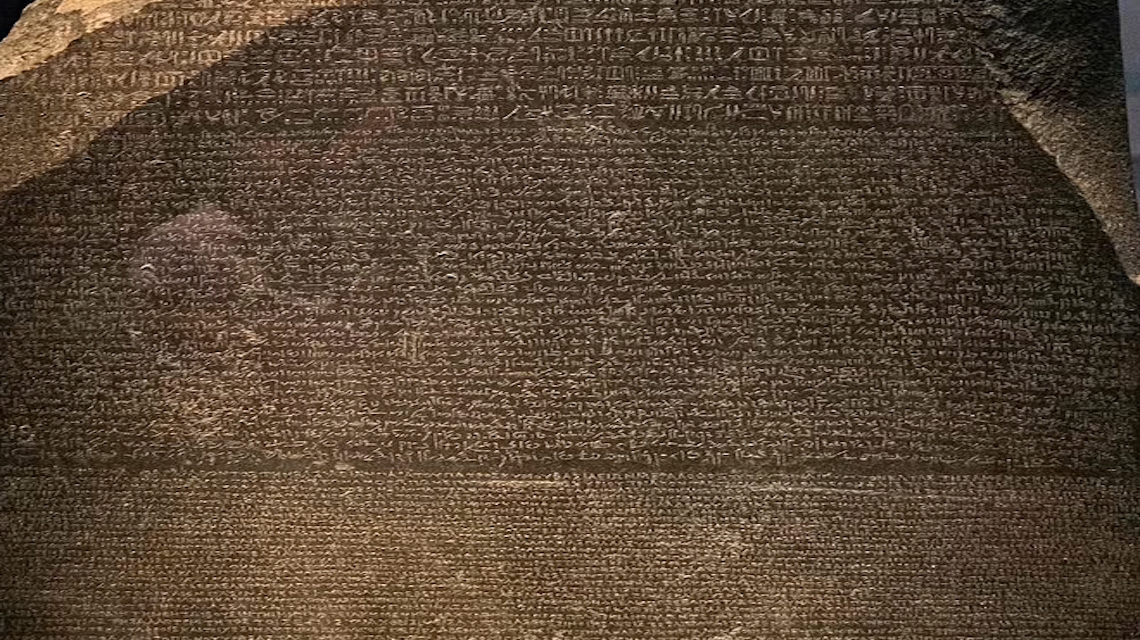

The turning point came in 1799, during Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign in Egypt. Near the port town of Rashid (Rosetta), French soldiers uncovered a slab of black basalt buried in the foundations of a fort. This artifact—later named the Rosetta Stone—stood 114 centimeters tall, 72 centimeters wide, and 28 centimeters thick, covered in inscriptions in three distinct scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek. The Greek text offered a fully understood linguistic reference; the demotic, the script of everyday Egyptians, provided a bridge between sacred hieroglyphs and spoken language; and the hieroglyphs themselves, previously indecipherable, now had the potential for comparison. The Rosetta Stone became more than an artifact—it became a linguistic key, the ultimate puzzle poised for human ingenuity.

Early Theories and False Starts

The early response to the Rosetta Stone was a mixture of excitement and frustration. Scholars rushed to study it, but progress was slow. The prevailing assumption, inherited from antiquity, was that hieroglyphs were purely symbolic. Ancient Greek historians like Horapollon had described hieroglyphs as allegorical or mystical signs, a view that persisted for centuries. Some 16th- and 17th-century European scholars even tried to match hieroglyphs to Latin letters arbitrarily, producing fanciful yet meaningless interpretations. Others believed hieroglyphs conveyed philosophical or religious truths in a symbolic rather than phonetic system. These early attempts, while imaginative, made little progress toward understanding the practical mechanics of the writing system.

The discovery of the Rosetta Stone offered the first opportunity for a systematic, evidence-based approach. By comparing the known Greek text to the Egyptian scripts, scholars could finally test their hypotheses. This was a paradigm shift: the goal was no longer to interpret symbolic meaning through intuition, but to apply scientific reasoning and rigorous cross-validation.

Cartouches: The First Clues

The first critical insight came from the discovery of cartouches—elongated oval loops enclosing groups of hieroglyphs. These symbols consistently appeared around royal names. Scholars hypothesized that cartouches contained names like “Ptolemy” or “Cleopatra.” By comparing the Greek text with the hieroglyphic sequences inside these loops, it became possible to propose phonetic values for individual symbols. This was revolutionary. Hieroglyphs were not merely ideograms; they could encode sounds, representing letters or syllables. Repeated sequences across multiple cartouches allowed researchers to map symbols to their corresponding phonetic values.

This principle—recognizing phonetics within a primarily symbolic script—was the foundation of modern decipherment. It suggested that hieroglyphs were a mixed writing system, incorporating phonetics, logograms, and determinatives to convey meaning efficiently. This insight laid the groundwork for future scholars to tackle the system methodically.

Thomas Young: Systematic Observation

Among the first to exploit the Rosetta Stone was Thomas Young, an English polymath whose intellect spanned physics, mathematics, and linguistics. Young approached the problem with a meticulous, experimental mindset. He compared hieroglyphs to demotic signs and Greek letters, noting repeating patterns. He observed that foreign names frequently used phonetic signs, while native Egyptian words leaned on logograms and determinatives. Young proposed hypotheses for individual symbols, tested them across multiple contexts, refined them, and repeated the process—a rudimentary form of linguistic experimentation.

Young also categorized hieroglyphs into three functional groups: phonetic symbols (representing letters or syllables), logograms (representing entire words or concepts), and determinatives (clarifying semantic meaning without being pronounced). Though Young made significant progress—correctly identifying many phonetic signs in foreign names—he could not fully decipher native Egyptian vocabulary or grammar without a more complete understanding of the language.

Jean-François Champollion: The Coptic Connection

The decisive breakthrough came with Jean-François Champollion, a French linguist and prodigy in languages. Champollion had mastered Coptic, the last living descendant of ancient Egyptian. Coptic preserved pronunciation, grammar, and roots from its predecessors, providing a linguistic bridge between the ancient and modern. Champollion realized that understanding hieroglyphs required both phonetic decoding and comparative analysis with Coptic. This allowed him to test hypotheses systematically, rather than relying on intuition or guesswork.

Champollion began with foreign royal names like Ptolemy and Berenice. By mapping hieroglyphs to Greek letters, he confirmed phonetic values for individual symbols. He then cross-checked these values across other inscriptions, iteratively refining his mappings. This process exemplified early scientific verification: hypotheses were proposed, tested, validated, or discarded based on evidence.

Once phonetic symbols for foreign names were established, Champollion turned to native Egyptian words. Here, hieroglyphs were more complex, combining phonetic signs with logograms and determinatives. For example, the cartouche for “Ramses” included symbols representing R, M, and S, along with additional determinatives denoting “king” or “man.” This revealed the threefold functional structure of hieroglyphs: phonetics, logograms, and determinatives working together.

Mapping Vocabulary and Grammar

Champollion extended his analysis to ordinary words, administrative titles, religious terms, and common nouns. By comparing hieroglyphs to Coptic words, he reconstructed vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. For instance, the Coptic word for “sun,” re, corresponded directly to a specific hieroglyph. Through repeated analysis, patterns emerged in noun-adjective order, verb conjugation, and determinative placement. Hieroglyphs, it became clear, were highly context-dependent: the same symbol could serve as a phonetic letter, a logogram, or a determinative, depending on its position and surrounding symbols. Understanding context was crucial, much like decoding modern cryptographic systems.

Champollion applied cross-validation rigorously. Each phonetic hypothesis had to function consistently across multiple instances. Determinatives, too, were verified: words meaning “man” or “king” always included appropriate semantic symbols. This meticulous process transformed decipherment from speculative interpretation into systematic linguistic science.

Anecdotes and Lesser-Known Stories

Champollion’s journey was not linear. He worked tirelessly, often isolated, facing skepticism from peers. Some scholars dismissed his approach, arguing that hieroglyphs could never be decoded fully. In a dramatic 1822 announcement, Champollion sent a letter to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, detailing his discoveries. This moment is often romanticized as the “eureka” event of hieroglyphic decipherment. Yet behind the triumph lay years of painstaking cross-comparison, hypothesis testing, and linguistic reasoning.

Young, meanwhile, felt both pride and frustration. While he had laid the groundwork, Champollion’s Coptic-based approach completed the puzzle. Their combined efforts illustrate the cumulative nature of science: breakthroughs are rarely solitary but built on incremental contributions.

Scientific Principles in Decipherment

Champollion’s methodology can be described as linguistic cryptanalysis. He employed pattern recognition, comparative linguistics, iterative hypothesis testing, and contextual analysis. Cartouches acted as cipher keys, while Coptic provided the “known alphabet” to decode unknown symbols. By treating hieroglyphs as an integrated system rather than isolated symbols, he ensured that decipherment was rooted in logic, evidence, and replicable analysis.

This approach illuminated the functional sophistication of hieroglyphic writing. Unlike purely alphabetic systems, hieroglyphs could encode sound, meaning, and context simultaneously. Phonetic sequences allowed the representation of names and sounds; logograms conveyed ideas concisely; determinatives clarified semantics. The result was an elegant, multifunctional writing system capable of expressing complex administrative, religious, and literary concepts.