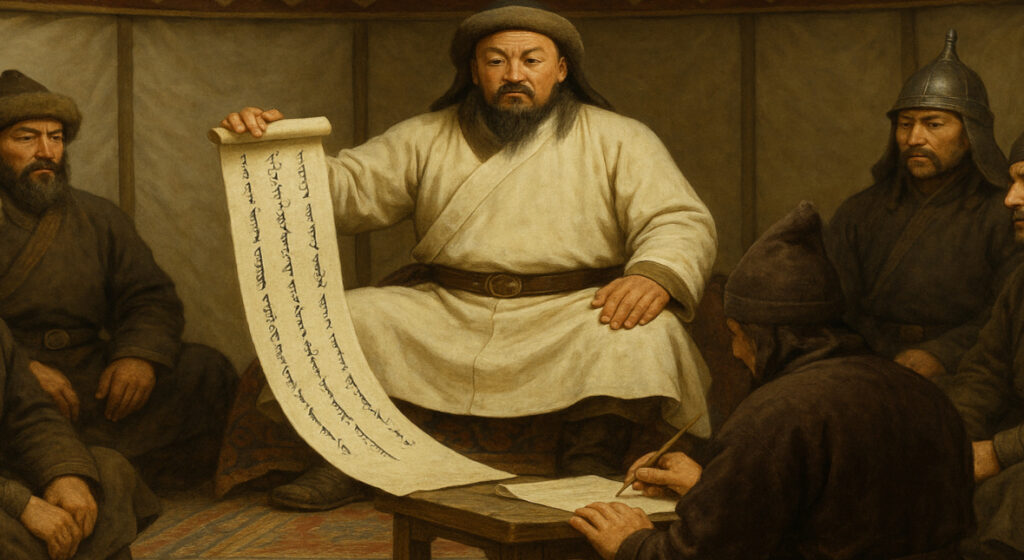

Amid the sweeping grasslands of Mongolia, where the wind races over endless plains and horses thunder beneath cloud-streaked skies, a once-fragmented tapestry of warring tribes came under the iron hand of a single, visionary leader: Genghis Khan. His rise was not merely the story of conquest but of unprecedented political and legal innovation. At the heart of this innovation was something almost mythic in its influence and secrecy—a law code known simply as the Yassa.

Far more than a list of rules, the Yassa was a tool of unification, a symbol of imperial authority, and one of the most mysterious legal constructs in world history. It helped build and sustain the largest contiguous land empire the world has ever seen, yet no original version survives. Even today, its nature eludes easy classification, hovering somewhere between oral tradition, military doctrine, and sacred decree.

The Birth of Yassa: Law Forged in Fire

The term “Yassa” likely comes from the Mongolian word for “decree” or “order,” reflecting its origin as the personal commands of Genghis Khan. According to medieval historians like Juvayni, Ibn al-Athir, and Rashid al-Din, Genghis Khan began to formulate the Yassa in the early 13th century, around the time he was proclaimed Khagan (universal ruler) of the Mongols in 1206.

In the wake of years of bloodshed, tribal betrayal, and shifting alliances, Genghis Khan understood that if he were to unify the fractious Mongol clans—and eventually, the vast territories beyond them—he would need more than brute force. He needed a system. A structure that would enforce loyalty, maintain order, and transcend ethnic, linguistic, and religious divisions.

And so, as his empire expanded across Asia, the Yassa grew with it—a set of laws and directives revised after each campaign, reflecting battlefield experience, statecraft, and Mongol tradition.

A Law Unlike Any Other

Unlike other great law codes in history—Hammurabi’s Code, the Twelve Tables of Rome, Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis, or China’s Tang Code—the Yassa was not carved on stone tablets or compiled into public scrolls. It was never meant to be seen by ordinary people. Instead, it was preserved in oral form or recorded in secret archives, accessible only to the Khan’s inner circle and administrative elite.

This secrecy was intentional and profound. By withholding the full text from the public, Genghis Khan ensured that the Khanate remained the sole interpreter and enforcer of law. The Yassa wasn’t simply a rulebook—it was a weapon of control. Its opaque and evolving nature made it nearly impossible to challenge or question.

What Did the Yassa Contain?

Although no complete copy survives, fragments of the Yassa were recorded by Persian historians, Chinese chroniclers, and European travelers such as William of Rubruck and Marco Polo. From these pieces, historians have reconstructed a rough outline of its contents—revealing a code that was at once practical, brutal, and visionary.

1. Military Discipline Above All

-

Soldiers who fled the battlefield or abandoned comrades were executed without mercy.

-

Looting was strictly regulated; all plunder was to be brought before commanders and distributed according to rank and need.

-

Any soldier who struck another in anger faced severe punishment—sometimes death—regardless of status.

The Yassa transformed the Mongol army into a highly disciplined, merit-based force, where obedience and cohesion were sacred. It is one of the key reasons the Mongols could defeat far larger and more technologically advanced armies.

2. Ruthless Justice

-

Theft, adultery, and bearing false witness were punishable by death.

-

Anyone found guilty of helping a fugitive could also be executed.

-

Murder, even in retaliation, was not permitted without state sanction. Personal vengeance was replaced by state justice.

While harsh, these rules imposed a sense of security and predictability in a world that had long been dominated by clan feuds and blood revenge.

3. Administrative and Civil Order

-

Regular censuses were mandated throughout the empire to assess population, collect taxes, and organize military drafts.

-

The Yam system, an imperial relay of postal stations, was protected by law and kept in meticulous order.

-

Tampering with official documents, horses, or goods was considered treasonous.

These measures facilitated one of the most efficient communication and logistics networks of the medieval world, allowing Genghis Khan’s commands to travel thousands of miles in a matter of days.

4. Religious Tolerance—Under Imperial Control

-

Religious leaders were granted freedom of worship and exemption from taxes or military service.

-

All major religions—Tengriism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and others—were tolerated, but none were allowed to challenge the supremacy of the state.

This was not born of modern pluralism, but of pragmatism: in a multiethnic empire, religious tolerance was a tool of stability. It also earned Genghis Khan surprising respect among the scholars and religious elites of conquered lands.

5. Social Engineering and Cultural Control

-

Marriage was strictly regulated. For example, kidnapping a wife or committing adultery carried the death penalty.

-

Nobles and commoners alike were subject to the same penalties—a radically egalitarian principle for its time.

-

Witchcraft, superstitious rituals, and fortune-telling were often banned, unless sanctioned by the state.

Through these laws, the Yassa sought to reshape society into a coherent unit. Mongol identity was prioritized, but mechanisms were built in to accommodate and assimilate foreign customs where useful.

A Living Law Code

One of the most fascinating qualities of the Yassa is that it was not static. It evolved with the needs of the empire and the vision of its rulers. New articles were added after each campaign. The laws changed with new regions, new challenges, new enemies.

This flexibility made the Yassa unlike any codified legal system in antiquity—it was more akin to an imperial operating system, updated by decree.

Even after Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, his successors—Ögedei, Möngke, and Kublai Khan—continued to invoke and modify the Yassa. In the Yuan Dynasty, for example, it was partially fused with Chinese legal systems, creating a hybrid governance model.

Mystery and Myth: Why Was It Kept Secret?

Historians still debate the reason for the Yassa’s secrecy, but several likely factors emerge:

-

Power Consolidation: By keeping the law obscure, the Khans remained the ultimate arbiters of justice.

-

Flexibility: A secret law can be altered without public backlash or contradiction.

-

Mythic Authority: The Yassa gained a kind of sacred aura—like divine law, known only to the chosen.

Some scholars suggest that Genghis Khan was deliberately avoiding the fate of other empires, whose published laws often became tools of bureaucracy and corruption. In contrast, the Yassa remained closely tied to the will and charisma of the Great Khan himself.

The Yassa’s Legacy

Although the original Yassa has been lost to time, its ideological and administrative impact echoed for centuries. It influenced:

-

The Ilkhanate legal reforms in Persia.

-

The development of state law in the Golden Horde (Russia).

-

The blending of customary and imperial law in Central Asia and China.

Elements of the Yassa even persisted into the modern period through oral tradition, folklore, and regional customs.

But perhaps its most enduring legacy is the lesson it offers in the nature of power: that empires are not held together by armies alone, but by ideas—by systems of belief, structure, and law, even when those laws are invisible.