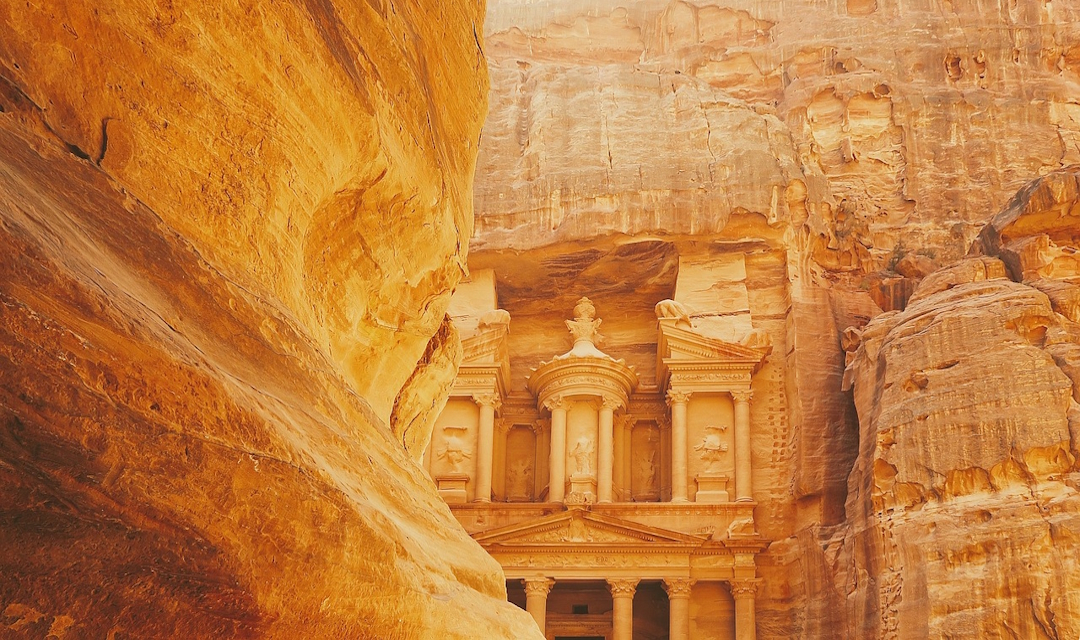

The Nabataeans transformed the arid canyons of Petra into a thriving oasis through an ingenious water management system. Situated in a deep valley surrounded by sandstone mountains, Petra has no perennial rivers; its scarce water comes from winter rains and a few springs. As UNESCO notes, “an ingenious water management system allowed extensive settlement of an essentially arid area during the Nabataean, Roman and Byzantine periods”. This system sustained a city of 30,000–40,000 people in a region with only ~6 inches of annual rain. By balancing flood control with year-round supply, the Nabataeans ensured that no drop was wasted.

The success of Petra was deeply tied to its water engineers. The Nabataeans—originally nomadic caravan traders—rose to power around the 4th–3rd centuries BCE along trade routes between Arabia, Egypt and the Mediterranean. Their capital became fabulously wealthy from incense and spice trade, but surviving in the desert meant mastering every available water source. Archaeological evidence confirms that “it was the ability of the Nabataeans to control the water supply that led to the rise of the desert city, creating an artificial oasis”. Remarkably, by integrating cutting-edge techniques borrowed from cultures they traded with (Hellenistic, Roman, Persian, Egyptian) and their own innovations, the Nabataeans engineered one of antiquity’s most sophisticated hydraulic networks.

Environmental Challenges in Petra

Petra lies in a hyper-arid environment. The city’s valley is crossed by Wadi Musa (Moses’s Wadi), a seasonal torrent that flows only during winter rains. For much of the year, “the whole site of Petra is devoid of perennial water flows”. Summers (June–September) are dry, and vegetation relied on stored water. Conversely, intense short rains cause violent flash floods in the wadis. A major flood from Wadi Musa once swept through the narrow Siq gorge and destroyed earlier water conduits. Thus the Nabataeans faced a dual challenge: capturing and storing the few months of rain for dry-season use, while protecting the city from destructive floods.

Local geography offered some advantages and hazards. High mountains west and east of Petra held small springs (Ain Musa, Ain Umm Sar‘ab, Ain Braq, etc.). The Nabataeans channeled these spring sources toward the city – for example, by a 7 km stone channel carrying the waters of Ain Musa and Ain Umm Sar‘ab to the entrance of the Siq. But the valley floor also acted as a funnel: floodwaters from several wadis could inundate Petra. The Nabataeans therefore designed elaborate flood-control works (dams, bypass tunnels, terraces) to prevent damage, while also feeding captured water into their distribution system.

Components of the Nabataean Water System

The Nabataean system combined catchment, storage, purification, and distribution. Key components included:

Dams and Diversions – small and large dams built across wadis and gullies to collect runoff. (See Bab as-Siq Dam and Al-Mudhum tunnel below.)

Channels and Aqueducts – carved or built conduits for moving water from springs and flood sites. Some were open rock-cut canals; others were buried pipeline segments of clay or stone.

Cisterns and Reservoirs – hundreds of rock-cut storage tanks in the city and surrounding hills, often underground or shaded, to hold water for dry months. (One scholar counted over 200 cisterns/reservoirs and more than 200 km of pipes in Petra.)

Settling Basins and Filters – sedimentation basins at inlets and along channels to slow flow and let silt settle out, ensuring clean water.

Distribution Tanks and Fountains – once water reached Petra, distribution tanks (castella) and public fountains/monuments acted as distribution points and displays of wealth.

The Nabataeans optimized each element with advanced design. Their pipelines used tapered-end ceramic pipes (jointed without mortar) – an innovation not seen again in the West until two millennia later. Open-channel flows were used wherever possible to minimize leakage; pipes were laid with very gentle slopes so that pressure built slowly. For instance, along the main Street of Facades, archaeologists observed that over a long downhill stretch, the road level drops dramatically but the water pipe descends only gradually – maintaining the water head and pressure in the city center. In effect, the Nabataeans designed the system to deliver a stable, near-maximum flow matching each spring’s capacity, avoiding turbulent surges or wasted pressure.

Catchment and Flood Control

To harvest rainwater, the Nabataeans built dams (also called “cofferdams”) in strategic wadis. These ranged from small rubble barriers to the monumental Bab as-Siq Dam at the Siq’s entrance (see below). By impounding winter floodwaters, these structures retained water long enough to slowly absorb into the ground or channel it to storage. The sediment-rich floodwaters also silted up behind the dams, increasing the fertility of wadi bottoms – an effect noted as similar to basin irrigation in Egypt.

In particularly hazardous areas, they used diversion tunnels and terraces. The most famous example is the Wadi Mudhlim Tunnel at Bab as-Siq. After a devastating flash flood in the 1st century BCE ruined Petra’s early waterworks, the Nabataeans built a 12.8-meter-high dam across the Siq’s entrance. Beside it, they hewed a rock-cut tunnel (about 90 m long and 12.8 m high) that shunts floodwaters from Wadi Musa south into Wadi Mudhlim. This effectively diverted the bulk of flood flow around Petra’s entrance, sparing the city’s facades and monuments. A wide flat upstream area acted as a natural settling basin, further protecting the gateway. The dam itself was later rebuilt in 1964 (over the original) to protect against floods.

Elsewhere, the Nabataeans built multiple smaller dams and terraces on the hillsides. A British archaeologist notes that south of Petra at the Humayma site, terraced catchments captured runoff to store in cisterns. Terracing and hillside channels reduced slope erosion and directed more water into the system. All these measures multiplied Petra’s effective rainfall capture, turning stormwater into a reliable local resource.

Cisterns and Reservoirs

Captured water was stored in cisterns – carved rock chambers or built tanks that could hold thousands of liters underground or in protected areas. Hundreds of these cisterns dot Petra and its surroundings. Notably, the summit of Jebel Umm al-Biyara west of Petra is riddled with cisterns nicknamed the “mother of cisterns”. These bottle-shaped cisterns (narrow necks, wide bottoms) are attributed to the Nabataeans and earlier Edomite inhabitants, designed to minimize evaporation while maximizing depth.

Within the city, cisterns were often roofed or covered to reduce loss from the hot, dry air. For example, at Humayma (ancient Hawara) a series of large cisterns were roofed with stone slabs, preserving water through the summer. In Petra, many cisterns are underground and completely concealed; Bedouins today still find them full of water and safe from evaporation. The scale was vast: Ortloff’s reconstruction of Petra’s network identifies over 200 cisterns and reservoirs of various sizes. Combined with the dams, Petra’s total storage capacity could exceed tens of thousands of cubic meters.

Construction methods were remarkably precise. Walls were smoothed and sealed with waterproof plaster or cement (reputedly a secret Nabataean mix), and geometric accuracy was common. Even well shafts (local springs tapped by hand) were plaster-lined to prevent seepage. Each cistern typically had a settling pit at its inlet: a small chamber or low dam where incoming water slowed, letting heavy sediment drop out. Thus water entering the cistern was relatively clear. Overall, the storage system ensured water could be kept safely for months: as one source notes, “underground cisterns kept water safe from both evaporation and enemies”.

Distribution Channels and Pipelines

After collection and storage, water had to be distributed throughout the city. This was done by an extensive network of channels, pipes and aqueducts. The most famous channel runs through the 1.2 km long Siq entrance itself. Along the north side of the Siq path, a pressurized pipeline of terracotta (clay) tubes carried fresh spring water from Ain Musa into central Petra. On the south side, a covered channel carved into the rock was laid: water flowed under stone slabs, dropping gradually toward the city. Numerous small stone tanks (“stilling basins”) are visible in this channel, used to slow flow and precipitate lime and silt. Four of these basins along the way even served as drinking fountains for travelers. After an earthquake in AD 363, only the southern rock-cut channel was repaired, but it still testifies to Nabataean craftsmanship.

Beyond the Siq, Petra had pipe conduits running beneath its streets and aqueducts leading to its monuments. Archaeologists have found ceramic pipes with carefully tapered ends – a seal-and-socket design that modern engineers only “figured out in the last two hundred years”. Pipes were laid with slight downhill gradients; for example, surveyors noted that a 1 km stretch of road falls dramatically, but the water pipes along it descend at only a gentle 3° slope, maintaining water pressure. Where possible, the Nabataeans preferred gravity-fed open-channel or near-open-channel flow rather than fully pressurized pipes. Analysis shows they deliberately kept flows sub-critical (not full to the brim) to minimize leakage and friction: their engineers essentially ran the pipelines at close to maximum flow without creating damaging pressure surges.

Their hydraulic design also matched the springs’ output. For instance, the large spring Ain Musa could supply more water than a single pipeline could handle, so the Nabataeans built in head tanks and reservoirs as buffers. During floods of spring flow, water could be diverted to fill upper and lower cisterns instead of overflowing in the pipes. Computational analysis suggests the pipelines were segmented: each segment began at an open head-basin whose height set the flow in the next pipe stretch. In practice, this meant each pipeline section operated under its own local water head, making the flow stable and almost “critical” (maximal) in each part. These measures increased total flow to the city: by reducing back-pressure and friction in the last leg of the pipeline, the overall throughput from the spring could be maximized.

Water Purification and Maintenance

Maintaining water quality was vital. The Nabataeans used decantation basins at multiple points. As described by archaeologists, incoming spring or storm water was passed through one or more successive cisterns or basins to let sediment settle. The water flows were slowed (often by wall barriers) so that heavy particles dropped to the bottom. This “simple filtration” greatly improved clarity before storage. In fact, each cistern had an attached settling pit and low inlet wall to intercept grit. By preventing silt from entering the main tank, they avoided clogging pipes and needing frequent dredging.

A local official called the “Master of the Water” oversaw the system, ensuring it ran year-round. Regular maintenance – such as clearing basins of sand and inspecting tunnel intakes – was part of Petra’s civic life (inscriptions at some high-places mention water officials). The Nabataeans even built flush outlets in some ceremonial sites: at the High Place of Sacrifice, a channel and trough allowed offerings and runoff to be washed away. In sum, their water system combined self-cleaning design with institutional upkeep to function continuously despite debris-rich flows.

Case Studies of Petra’s Water Structures

Petra’s hydraulic network included many notable structures. Below are key examples illustrating Nabataean ingenuity:

Bab as-Siq Dam and Al-Mudhlim Tunnel (Wadi Mudhlim Bypass): As noted, after a 1st-century BCE flood destroyed earlier waterworks, the Nabataeans erected a 12.8 m high dam at the mouth of the Siq and cut a 90 m tunnel through rock to divert floodwaters. Rain from Wadi Musa now bypasses Petra via Wadi Mudhlim and Wadi Mataha, protecting the entrance and lower city. Niches at the tunnel’s end hint that this scheme was also ritually blessed (water was sacred to them). Today only ruins of this “Bab as-Siq” dam remain, but its principle – controlling flash floods – exemplifies their planning.

Siq Water Channels: Within the narrow Siq gorge, the Nabataeans carved a hidden conduit system. On the gorge’s north wall, they laid a pipeline of ceramic tubes transporting fresh spring water (from Ain Musa) into town. On the south wall, they chiseled an open U-shaped channel, then covered it with stone slabs to keep water clean. Along this channel were multiple sedimentation basins (still visible) where lime and particulates settled. Remarkably, after Petra’s earthquake of 363 AD only this southern channel was repaired; the carved passage stands as evidence that the Nabataeans’ Siq channel was seen as permanent core infrastructure.

Ain Musa Spring Pipeline: The Ain Musa spring (“Moses’s Spring”) – about 8–10 km east of Petra – was the city’s most reliable source. From it, a long pipeline (partly hidden in a trench) ran down to the Siq entrance. This pipeline had to maintain flow over a complex terrain. Modern analysis reveals the design: the pipe’s steepest sections are carefully angled to achieve critical flow (the highest stable velocity) from an upstream reservoir. At several points it intersects tanks and distribution cisterns (including one near the Sewer Cistern). As field studies show, by segmenting the pipeline and using intermediate tanks, the engineers could shut off sections to fill reservoirs or to shut down that stretch for maintenance. Thus in low-flow seasons they could prioritize storage; in high flow they let the system run full. In fact, Ortloff estimates that a large fraction of Ain Musa’s output could be sent through this main pipeline, with reserves remaining to refill cisterns during drought.

Humayma (Hawara) Aqueduct and Cisterns: South of Petra at Humayma, the Nabataeans built an immense waterworks. Canadian archaeologists report that rain-runoff was collected into huge cisterns (roofed to prevent evaporation) with upstream settling basins. Moreover, a 26.5-km long spring-fed aqueduct brought water to the town. This system – still partly functional today – highlights how Nabataean engineers applied the same principles at smaller settlements: catch runoff, purify, store, and channel spring water over great distances with no pump power.

Other Aqueducts and Fountains: In Petra’s later period, the Romans built monumental fountains (nymphaea) and baths. Archaeology shows that these also tapped into the Nabataean network. For example, an extension from the Siq pipeline leads to the Great Temple’s fountain plaza, and another feeds the Nymphaeum near the colonnaded street. Even the rock-hewn colonnaded street of Petra was originally equipped with an underground pipe to supply roadside nymphaea and public baths. These later constructions followed Hellenistic/Roman aesthetics, but relied on the same gravity-fed infrastructure that the Nabataeans pioneered.

Comparisons with Other Ancient Water Systems

The Nabataean system stands out, but its principles can be compared to other ancient cultures:

Roman Aqueducts: Like Romans, the Nabataeans used gravity and construction skill to bring water to cities. However, Roman aqueducts (e.g. in Caesarea, Jerash) typically carried massive flows from distant lakes or mountains through arches and siphons. In Petra’s hilly terrain, building long high aqueducts was impractical. Instead, the Nabataeans often routed water along the land surface or slightly buried it. Later, when Rome annexed Nabataea in AD 106, Roman engineers did add known techniques (like advanced pipe linings and new distribution tanks). Still, Petra’s unique constraint – extremely low and irregular input – meant that “while knowledge of hydraulic technologies from foreign sources was available, the rugged terrain, distant springs, and brief rains required technical innovations”. The Nabataeans solved problems (e.g. flow surge control, partial pressure pipes) that Roman engineers did not explicitly document, even though they met later in history. In short, Petra’s waterworks combined Greek/Roman influences with original solutions tailored to desert limits.

Persian Qanats: The Persian qanat is an underground gently sloping tunnel that brings groundwater to surface without evaporation losses. Qanats originated ~3,000 years ago in Iran and are still used today. They have advantages – namely a reliable year-round flow and immunity to evaporation and flood damage – but require an accessible aquifer. The Nabataeans’ springs (like Ain Musa) were effectively like small qanats’ outlets, but in Petra’s limestone it was easier to channel the spring flows by surface pipelines than to sink deep galleries. Unlike qanats, which tap aquifers, Petra’s system had to capture ephemeral surface water and a handful of springs. In that respect the Nabataeans developed the opposite strategy: collecting seasonal runoff with dams and storing it, rather than relying on groundwater. Both approaches – Persian qanat and Nabataean open-channel – show the ingenuity needed to live in arid lands, each optimizing for local conditions.

Egyptian Nile Irrigation: Ancient Egyptians famously harnessed the Nile’s annual flood with basin irrigation: they built earthen banks and canals to direct predictable inundation into fields. The flood was regular and silt-rich, replenishing soil fertility. In contrast, Petra’s rainfall was infrequent and destructive. Egypt’s system aimed at agriculture on floodplains, whereas Petra’s system aimed at supplying a city and its gardens. Egyptian farmers could rely on precise flood timing, but Petra’s engineers had to be ready for any storm, and then store that water for long droughts. One similarity is that both used gravity and simple engineering: Egyptian dams were like large-scale basins, while Nabataean cofferdams mimicked micro-basin irrigation by capturing sediment and moisture on slopes. But overall, the technological needs were different – Egyptians sought controlled fertilization of fields, while Nabataeans sought controlled irrigation and preservation of water for urban life.

Indus Valley and Other Early Systems: Interestingly, historians have noted that the Nabataeans’ use of sequential settling basins and covered tanks echoes water practices in much older civilizations like Mohenjo-Daro and Knossos. However, those systems also developed in riverine contexts. Petra’s water network was unique in being one of the most advanced for a true desert city, integrating dozens of dams with hundreds of cisterns and kilometers of pipeline. In its complexity and scale – supporting 30k people in the wasteland – Petra rivals great Roman or Persian projects, which underscores Nabataean skill.

How did Petra keep flowing water through the dry summer?

The strategy was storage plus continuous supply. Every flood or rain was immediately channeled into cisterns and filtered basins. In the absence of rain, spring-fed flow (especially from Ain Musa) was regulated to supply fountains and baths steadily. The abundant underground storage (roofed cisterns) ensured that even in July the city still had fresh water and could irrigate gardens. An ASCE landmark summary notes that “in a desert region where annual precipitation is only 6 inches per year, [the Nabataeans] learned how to utilize channels, cisterns, [flow] pipelines and reservoirs to supply a major population center with a constant water supply throughout the year”.

In practice, this meant a well-managed schedule: during the wet season, pipelines and dams were opened to capture and direct runoff. Sediment was flushed out regularly via sluices. The settling basins had cleaning grates to remove silt deposits, keeping the system unclogged. Workers (or slaves) would maintain the network, much as in Roman cities a “master of water” was known to oversee maintenance. In the dry season, water release was controlled to conserve reserves. The nearly-closed basins and underground tanks kept evaporation losses to a minimum. Some monumental fountains (like the Great Temple’s) could be shut off to save water when needed.

Overall, the maintenance protocols were implicit in the design: decantation basins reduced the need for constant sweeping of sediment; sealed tanks reduced loss; and segmentation allowed parts of the network to be isolated if repairs were needed. These features ensured Petra’s aqueducts and cisterns remained serviceable for centuries – a marvel that even impressed ancient writers like Strabo, who marveled at Petra’s “abundance of springs” despite its location.

Modern Legacy and Applications

Today, Nabataean water technology continues to inspire engineers and conservationists. In Jordan and beyond, scholars and practitioners note that ancient solutions can aid modern sustainability. For example, one water engineering blog highlights how modern prairie farmers face analogous challenges of capturing sporadic runoff and storing it. It points out that Nabataean methods – strategic cistern placement, settling basins to prevent siltation, and capturing snowmelt – have direct parallels to improving modern water reservoirs. Already, Jordanian authorities and international experts are revitalizing Petra’s ancient network: old dams are being repaired and silted channels cleared to protect the site from floods and enhance groundwater recharge.

More broadly, the principle of maximizing capture and minimizing loss is timeless. The Nabataeans “learned how to utilize channels, cisterns, [and] reservoirs” in tandem – a lesson applicable to arid-region engineering today. For instance, covering canals or lining them (as Nabataean cisterns were plastered) can greatly reduce evaporation. In Israel and Syria, systems called khettaras or falaj (similar to qanats) have been re-evaluated using Nabataean knowledge. Even California’s modern aqueduct projects discuss ideas like shading water conduits to curb evaporation, reminiscent of how Petra’s channels were covered by stone slabs.

Finally, the cultural legacy persists. Many Nabataean cisterns and water monuments are now conserved archaeological sites. The very fact that Petra’s fountains and cisterns drew the attention of UNESCO in its World Heritage designation underscores the universal value of this heritage. In Saudi Arabia, the rediscovery of Nabataean wells in AlUla is celebrated as a marvel of desert engineering, and tour guides routinely point out how these ancient technologies still lie at the heart of the Middle East’s water stories. In summary, the Nabataeans’ waterworks are not just a historical curiosity; they are a blueprint for sustainable water use in harsh climates, tested and proven in one of the driest seats of antiquity.

Sources: Technical and historical details above are drawn from archaeological surveys and engineering studies of Petra’s water network, as well as comparative analyses of ancient hydraulic systems. This comprehensive review incorporates recent research (including hydrodynamic modelling of Petra’s pipes) and field studies by experts such as Ortloff, Oleson, and Harvey.

Citations

Petra – UNESCO World Heritage Centre

Petra | ASCE

Nabataean architecture – Wikipedia

The Ancient City of Petra | AMNH

Nabataean architecture – Wikipedia

Hydraulic Engineering at 100 BC-AD 300 Nabataean Petra (Jordan)

Dam and Mudhlim tunnel, Petra. Art Destination Jordan

PETRA: Water Works

Hydraulic Engineering at 100 BC-AD 300 Nabataean Petra (Jordan)

How ancient water management techniques may help Prairie farmers experiencing drought

The Ancient City of Petra | AMNH

Nabataean | Nabateans Saudi Arabia | Saudi Arabia Nabatean City

Hydraulic Engineering at 100 BC-AD 300 Nabataean Petra (Jordan)