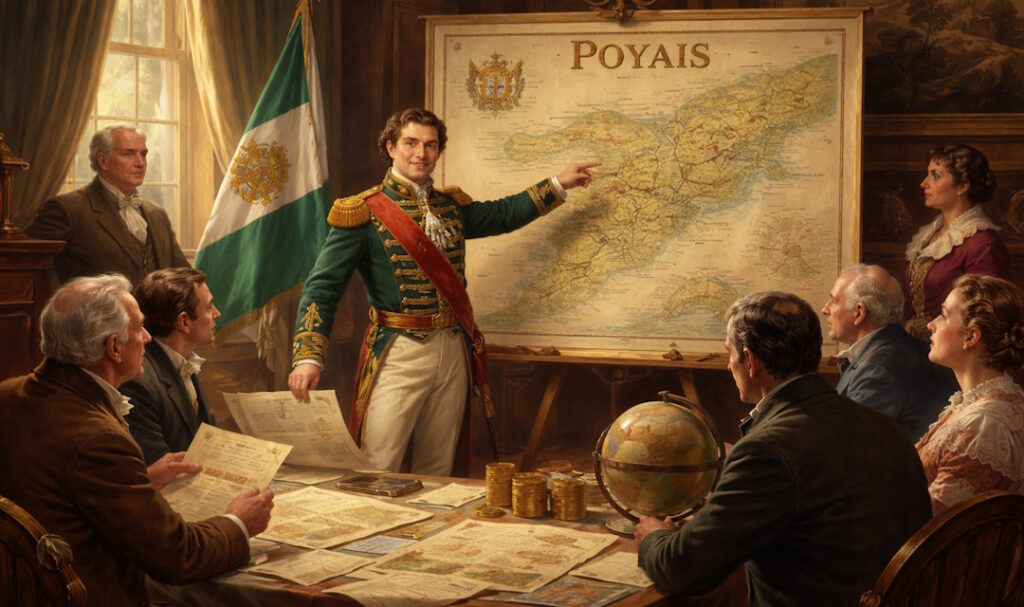

In the early 1820s, the British public was fascinated by exotic lands, colonial ventures, and the promise of wealth in distant territories. Into this atmosphere stepped Gregor MacGregor, a Scottish adventurer, soldier, and master of persuasion, who would execute one of history’s most audacious deceptions. He convinced dozens of people that a country called Poyais existed on the Mosquito Coast of Central America, a land of fertile soil, friendly natives, and thriving cities. At the center of this scheme was a 355-page guidebook: Sketch of the Mosquito Shore, Including the Territory of Poyais, Chiefly Intended for the Use of Settlers.

The book was attributed to Thomas Strangeways, aide-de-camp to His Highness Gregor, Cazique of Poyais, but in reality, neither Strangeways nor Poyais existed. The authorship was MacGregor’s own, or more precisely, his plagiarism of other contemporary books on Central America. He borrowed sections from travelogues, geographical surveys, and colonial reports, weaving them into a convincing narrative about a country brimming with resources, infrastructure, and opportunity. Every detail was carefully curated to suggest that Poyais was not merely real, but thriving and ready for settlement.

The guidebook opened with descriptions of the capital, St. Joseph, a city that existed only on paper. According to the text, St. Joseph had paved streets, grand squares, courts of law, churches, and even an opera house, conveying the impression of European-style civilization transplanted into the tropics. Settlers reading the book could imagine themselves walking along the broad boulevards or attending cultural events, completely unaware that the city’s streets were dense jungle and swamps. The level of detail created a sense of credibility that few dared to question.

Beyond urban planning, the guidebook included meticulous accounts of Poyais’ climate, geography, and natural resources. Rivers, lakes, and mountains were named, water depths recorded, and forests described as teeming with edible plants and timber. Wild game roamed freely, while untapped gold and mineral deposits promised wealth for those industrious enough to exploit them. MacGregor’s book suggested that settlers could expect both sustenance and opportunity with minimal effort—a powerful lure for families and investors alike.

The supposed indigenous inhabitants, the “Poyers”, were also described in the guidebook. MacGregor depicted them as cooperative and industrious, trading goods instead of demanding currency. This fictional portrayal not only added to the sense of civilization but also assuaged European anxieties about encountering “hostile natives.” It was a clever psychological tactic: by presenting the locals as helpful, the land felt safe and welcoming, further reducing skepticism.

To strengthen the illusion, MacGregor included maps, flags, and even a national currency. The maps were detailed and convincing, showing St. Joseph as a hub of activity with roads, ports, and smaller settlements along the coast and rivers. The flag, usually depicted in blue, white, and red with a central crown emblem, gave a visual symbol of sovereignty, while the Poyais dollars featured official seals and denominations. Together, these tangible items allowed investors and settlers to interact with the fantasy, making it seem materially real.

MacGregor’s marketing strategy was equally sophisticated. He distributed the guidebook widely, ensuring it reached newspapers, banks, and the British elite. Excerpts appeared in print as if independently verified, lending the scheme legitimacy. Britain, still recovering from the Napoleonic Wars, had thousands of veterans unemployed and restless. The guidebook promised them fertile lands, social status, and economic opportunity. It sold not only land but hope and status, an irresistible combination.

The financial angle was particularly clever. MacGregor sold land certificates and government bonds, presenting them as legitimate investments in a sovereign nation. Banks endorsed the venture, investors purchased bonds, and settlers booked passage with confidence. Few questioned whether the capital or infrastructure actually existed; the authority of the printed word, maps, and symbols seemed sufficient. Paper became proof, and belief became reality.

In 1822, the illusion tragically collapsed. Settlers arrived at the supposed Poyais only to find dense jungle, swamps, and disease. There were no streets, no buildings, no government officials. The opera house and courts were nowhere to be found. Malaria and yellow fever spread rapidly, and starvation set in. Many settlers died before rescue ships carried the survivors back to Britain, leaving behind shattered families and ruined fortunes. The book that had promised paradise had instead guided people into catastrophe.

Even after the disaster, some settlers refused to accept that Poyais was imaginary. They argued that poor navigation or management, rather than fraud, had caused the failure. This demonstrates the power of MacGregor’s book: it shaped belief so strongly that reality itself became negotiable. The persuasive force of exhaustive detail, official symbols, and confident narration had created an illusion that could survive physical evidence to the contrary.

Despite the deaths and financial losses, MacGregor escaped almost entirely unpunished. The law at the time could not easily prosecute someone for selling a country that existed only on paper. He later attempted the same scheme in France, producing new maps, documents, and guides. Eventually, he returned to Venezuela, where he was treated as a respected military veteran. He died in 1845, largely unscathed by the human and financial cost of his deception.

Find book here: Sketch of the Mosquito Shore, Including the Territory of Poyais