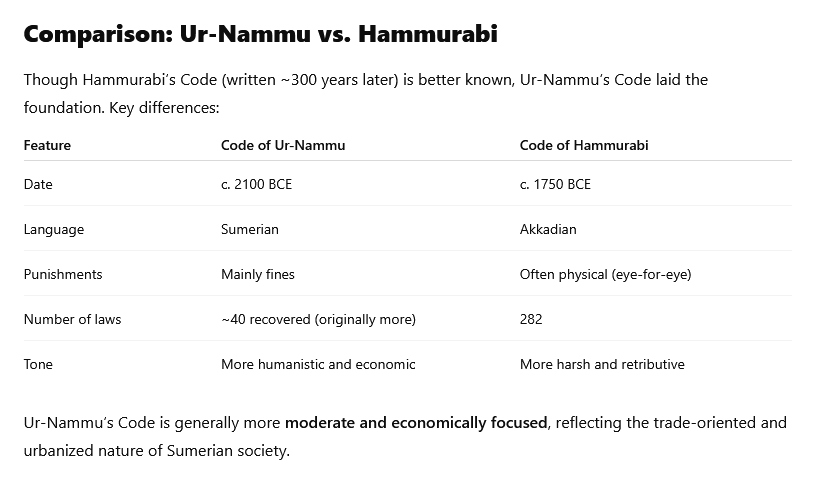

Law is one of humanity’s greatest inventions—an agreed-upon framework to ensure order, resolve conflict, and govern society. Long before modern constitutions and legal systems, and centuries before the biblical Ten Commandments or the more famous Code of Hammurabi, there was a remarkably advanced and humane legal document born in the cradle of civilization: the Code of Ur-Nammu.

Written more than 4,000 years ago in the Sumerian city of Ur, in present-day Iraq, the Code of Ur-Nammu is widely regarded by historians and archaeologists as the oldest known legal code in human history. Though only fragments of the original text have survived, this ancient code offers stunning insight into early Mesopotamian justice, societal values, and governance.

The Historical Context: The City of Ur and the Sumerian Renaissance

To fully appreciate the Code of Ur-Nammu, one must step into the ancient world of Mesopotamia, specifically during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112–2004 BCE). This was a period of political unification, economic flourishing, and religious revival after centuries of city-state rivalries.

King Ur-Nammu, who ruled from around 2112 to 2095 BCE, founded the Third Dynasty of Ur following a power vacuum left by the decline of the Akkadian Empire. Under his rule, Ur became a center of power, innovation, and culture. Ur-Nammu initiated massive building projects—temples, ziggurats, irrigation canals—and laid the groundwork for a highly organized bureaucratic state.

But his most profound legacy may not be architectural, but juridical: his legal code.

Discovery of the Code: Ancient Tablets in a Modern World

The fragments of the Code of Ur-Nammu were not found in a single intact document. Rather, they were pieced together over decades from clay tablets excavated at several Mesopotamian archaeological sites, particularly:

- Nippur, a major religious center where scholars believe the code was widely copied.

- The Istanbul Archaeological Museums, where critical tablets are held.

- The Penn Museum in Philadelphia, which houses further fragments.

These tablets are inscribed in Sumerian cuneiform, the world’s earliest known system of writing, impressed onto wet clay with a stylus made of reed. Due to damage and gaps in the tablets, scholars had to cross-reference these fragments with other contemporary texts to reconstruct the code.

The translation and interpretation of the Code have been primarily attributed to Assyriologists such as Samuel Noah Kramer, Jacob Klein, and Miguel Civil, who dedicated years to reconstructing the legal logic, linguistic nuance, and historical significance of the text.

Language and Structure of the Code

The Code was written in Sumerian, the language of ancient southern Mesopotamia. Though long extinct, Sumerian has been deciphered through its use in thousands of administrative, literary, and religious tablets. The code uses a casuistic format—“if… then” statements—which would become the standard for ancient law collections.

The Code is structured into three parts:

1. Prologue (Royal and Divine Justification)

The code opens with a preamble in which Ur-Nammu explains that he was chosen by the gods An (sky god) and Enlil (lord of the wind) to restore justice and eliminate lawlessness. He presents himself as a divine agent of justice who brings balance to society.

“When An and Enlil had given Ur-Nammu the kingship of the land, to establish equity and justice…”

This divine framing is important—it aligns the king’s authority with cosmic order, legitimizing his laws as more than human decrees.

2. Body of Laws (Case Laws)

The core of the code consists of approximately 40 legal provisions, although the original may have included more. These cover civil, criminal, family, and commercial law. Each law follows the logical pattern:

If [a condition occurs], then [this consequence shall follow].

Here are examples:

Capital Crimes:

“If a man commits a murder, that man must be killed.”

“If a man commits robbery, he shall be killed.”

Bodily Harm:

“If a man knocks out the eye of another man, he shall weigh out half a mina of silver.”

Sexual Offenses:

“If a man violates the rights of another man’s wife, he shall pay five shekels of silver.”

Slavery:

“If a slave marries a free woman, he shall hand the first-born son over to his owner.”

False Accusation:

“If a man falsely accuses another, he shall pay fifteen shekels of silver.”

3. Epilogue (Likely Lost)

Unlike later codes, such as Hammurabi’s, no full epilogue survives from Ur-Nammu’s code, though scholars suspect it may have included further moral or theological justification.

Unique Features of the Code of Ur-Nammu

What makes this code stand out—especially for its time—is not just its age, but its sophistication and humaneness. Here are its most notable characteristics:

● Primacy of Fines over Physical Punishment

Unlike later codes such as Hammurabi’s, which often relied on lex talionis (“eye for an eye”), Ur-Nammu’s system favored monetary compensation. Most offenses that today might be met with physical penalties were instead resolved by weighing out silver.

This suggests a society where property, commerce, and civil restitution were highly valued—possibly due to the economic centrality of trade in Sumerian cities.

● Legal Protection for the Vulnerable

The prologue emphasizes protection for widows, orphans, and the poor. This was not a purely moral gesture but a political one—ensuring loyalty from the broader population while reinforcing the king’s divine responsibility.

● Standardized Weights and Measures

By setting fines in specific weights of silver (shekels, minas), the code also functioned as a tool for economic standardization, helping unify trade practices and value systems across the kingdom.

● Concept of Intent and Consent

Some laws show an early awareness of intent, differentiating between consensual and non-consensual acts—especially in the context of sexual relations or marriage violations. This adds nuance rarely seen in such early legal texts.